In studies comparing instructional tools and how they support online teaching, educators have stressed the importance of tools that support specific tasks, and thus allow more flexible teaching, facilitate access to resources and peers, and promote collaborative learning (Britain & Liber, 1999; Harasim, 1999; Bonk, 2001).

To investigate how online instructors use instructional tools designed for the Web, we conducted a study with a group of 32 online instructors to address the following questions: (1) What tools are most commonly used by online instructors? and (2) What are the advantages and the disadvantages of online tools as perceived by online instructors? Respondents filled out an online questionnaire (Exhibit 1) and we conducted follow-up interviews with six respondents chosen on the basis of their availability (Exhibit 2).

While this study was conducted with a small group of instructors, these are online instructors with years of experience in online teaching and the use of Web resources. Their data provide new and insightful views on the use of instructional Web tools.

Questionnaire respondents

Participants in the study are instructors who teach in either mixed mode or entirely online mode. By "mixed mode," I refer to courses in which some class sessions are offered face-to-face while others are offered online; by "entirely online mode," I refer to courses in which there are no face-to-face class sessions. All respondents have had more than three years of online teaching experience and have taught in the place-based classroom.

Respondents include online instructors from Canada, the United States, Mexico, the Netherlands, Greece, Colombia, Spain, the United Kingdom, Australia, and South Africa. Formal consent was obtained from all the instructors who participated in the study. Most instructors were associated with the TeleLearning Network of Centres of Excellence in Canada, but we sought online instructors in other countries through Internet mailing lists (listservs) such as Distance Education and Active Learning (ACTIVE), and the Distance Education Online Symposium (DEOS). We used e-mail messages to ask them to access the questionnaire on our home page and to complete and submit it online. We then explored questionnaire findings and asked respondents to be available for a follow-up interview to validate results. While the results of this study cannot be generalized for the entire population of online instructors, they do provide useful information about online instructional tools and how they are used.

Each of the 32 respondents teaches one online course. Of these 32 courses, 18 were taught entirely online and 14 were taught in mixed mode. Half of these courses (16) were taught by an instructor plus a teaching assistant, and the other half (16) were taught by one instructor only (see Figure 1).

Of the 32 university and college instructors who responded to our survey, 20 (63%) were male, and 12 (37%) were female. Nearly half of them were between 41 and 50 years of age. With regard to course level instruction, 17 respondents were teaching undergraduate level courses, 8 taught graduate level courses, and 4 taught a combination of the two; 3 respondents answered "other" for this item of the questionnaire.

Results

Below we summarize and discuss our results in a research framework similar to that used in Teles, Ashton, & Roberts (2000) on the instructional, managerial, social, and technical dimensions of the role of the online instructor.

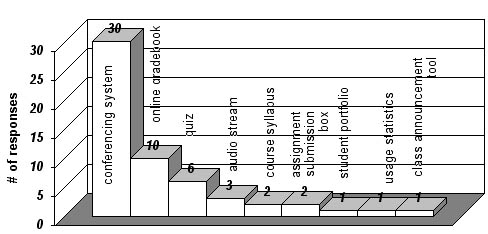

The majority of instructors selected tools that support course coordination and management as those they most commonly use. Such tools include those that assist in distributing tests and evaluation forms, recording grades, giving and receiving assignments, and providing an overview of student participation through usage statistics. The figure below shows instructors' preferences.

The Selected Tools

A conferencing system is an asynchronous communication medium that allows instructors to design and teach classes in the online classroom. Examples of conferencing systems are WebCT, Blackboard, Virtual-U, FirstClass, and many others. The Centre for Curriculum, Transfer and Technology in British Columbia, Canada, has a Web site that describes and compares the most viable computer conferencing systems according to the following criteria: technical specifications, instructional design values, tools and features, ease of use and accessibility, potential for collaboration, and IMS metadata standards compliance.

The online gradebook is a tool that allows instructors to post grades so that students can view their own grades and see the grade distribution, including average, low, and top grades. Bar charts are used to show grade distribution.

Quiz is used here as a generic name for interactive online exercises. Instructors may design multiple-choice questions with immediate feedback, or employ such other options as short-answer, jumbled-sentence, crossword, and fill-in-the-blank exercises.

Audio stream is a tool for asynchronous audio, which makes it possible for students to listen to pre-recorded messages via the Web.

Course syllabus is a course outline that details the subject area to be covered, required class projects, tests, readings, and other activities associated with the online course.

In the online assignment submission box students are asked to place class assignments so that the instructor can retrieve them.

The student portfolio can be accessed only by the individual student and the instructor. In the student portfolio, students keep class information, grades, and instructor's comments. In some systems, the student portfolio can also be accessed by administrators.

Usage statistics is a tool that collects usage data for each student and keeps track of the interactions in the classroom: when a message was written and to whom, how many messages a student has written, how many instructor's messages were received, the date and time when each student logged on and for how long, which classroom areas the student went to, and the time spent in each area.

The class announcement tool is used to send reminders of due dates for assignments, exams, and other class activities.

Respondents chose conferencing systems and the online grade book as the two most used tools. The fact that 30 respondents use conferencing for course delivery shows how this practice has become an established choice, as opposed to e-mail, mailing lists, and Web pages, which were common methods for delivering online courses in the last decade.

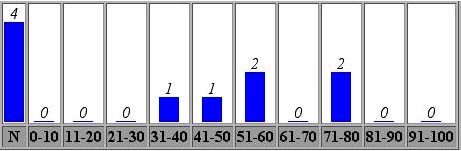

The online gradebook is the second choice for the most useful tool. If developers further enhance and improve gradebooks according to the needs expressed by instructors, this tool can become much more comprehensive and functional in the future. Some of the gradebooks show grade distribution, which enable students to identify how their grades compare with others in the course. In the grade distribution below for a class task, four students had not completed the task and were not graded; one student was graded 31-40, one received 41-50, two had a 51-60 grade, and the top two students were graded 71-80.

Twenty-seven (84%) of the instructors responded that they use tools to support their online teaching, 22 (70%) of them expect to use the same tools the next time they teach online, 7 (20%) stated they will use the same tools and new ones as well, and 3 (10%) expect to use fewer tools next time they teach online.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Tools

The major advantages of online instructional tools identified by respondents are that they offer flexibility and can be easily accessed in the online classroom, and that they support the flow of communication and the sense of community in the online classroom. Instructors also mentioned that instructional tools provide structure and unity to the course while empowering students—for example, by giving them access to grade distribution for the entire class.

Some of the comments made by the instructors regarding the advantages of online tools are: "They are flexible and extend the interaction, making students' thinking more visible"; "They increase communication and the sense of community in the online classroom"; and "They provide students with more time for reflection and this allows me to better integrate appropriate instructional design strategies" (see Exhibit 3).

The disadvantages of online instructional tools as identified by respondents include technical and administrative problems and the amount of time required to implement and use them. Respondents also noted that they are not customizable and impose pedagogical rigidity. Some of the comments made by respondents regarding disadvantages of online tools are: "More preparation time is required," "Some tools require a lot of extra time to implement and then manage the tasks," "Delivery platforms have rigid structures that do not accommodate designs a teacher wants to implement," and "Using some of these tools also implies more occurrences of technical and administrative problems" (see Exhibit 4).

Recommendations for the Development of Online Tools

Instructors stated that their experience has shown that more functional, user-friendly tools are needed to support their teaching. Respondents also mentioned some of the tools they would like to see developed and made available, citing such features as instructional design, role-play, debate organizer, plagiarism checking, brainstorming, conferencing with wireless application protocol (WAP), integrated spellcheckers, real-time group discussion, and analytical tools. An easy-to-use learning management system was also mentioned by many respondents as a tool they need.

The majority of the new tools or additional features recommended by instructors are related to the pedagogical and managerial roles of the online instructor. The online teaching workload—that is, the amount of time spent teaching online compared with the amount of time spent teaching (and preparing classes) in the place-based classroom—is an important issue as well. As most respondents stated that they dedicate more time to managerial functions when teaching online, they also observed that their teaching workload is greater in the online classroom. This remains consistent with our previous findings (Teles et al., 2000), which indicated that managerial tasks took up more time than the provision of instruction. Among the reasons that may explain their present observations are an absence of administrative or technical support, poor design of some tools and delivery platforms, or lack of training programs to teach instructors how to use tools to support online teaching.

There is an established procedure to set up face-to-face classrooms for instructors. Staff clean the classrooms, organize desks in rows, and bring supplies such as chalk. There is a media center in charge of supplying equipment such as projectors, TVs, and tape recorders; there are also clerical staff who manage and update class lists, grades, and courses. All of these supports allow instructors to focus on teaching without worrying much about administrative and classroom management tasks.

In the online classroom, however, the instructor in most cases has to perform all the management and instructional tasks, to provide technical advice to students, and to facilitate the process of socialization. While some educational institutions are beginning to provide support for online instructors, this process is still in its early stages and there are no comprehensive, generally accepted policies to support online instructors.

Results also point to the need for new research to investigate the use of tools for online teaching: what online teaching tasks can be supported by tools, how these tools can support instructors who want to develop their own instructional methodologies, and how improved evaluation tools can support online instructors in classroom monitoring and student assessment.

Instructional tools that are too complex to learn or too time consuming are less attractive for instructors than those that are more intuitive and easy to use. More studies are needed to assess the value of the most commonly used instructional tools and to identify areas for development in the ways these tools can support online instructors.

References

Bonk, K. (2001). Profs want better web tools. So what are they? Retrieved March 25, 2001, from http://www.sfu.ca/cde/Teles/TELElearn/TLN_IE/office.html

Britain, S., & Liber, O. (1999). A framework for pedagogical evaluation of virtual learning environments (JTAP Rep. No. 41). Report prepared for JISC Technology Applications Programme. Retrieved June 21, 2000, from http://www.jtap.ac.uk/reports/htm/jtap-041.html#Toc463843840

Harasim, L. (1999). A framework for online teaching: The Virtual-U. IEEE Computer, 32(9), 44-49.

Teles, L., Ashton, S., & Roberts, T. (2000). Investigating the role of the instructor in online collaborative environments (Research Project 5.25). Vancouver: The TeleLearning Network of Centres of Excellence. Retrieved July 20, 2000, from http://www.telelearn.ca/g_access/research_projects/index_th5.html

word gamespc gamesadventure gamesbrick busterplatform gamescard gamessimulation games